How to critically appraise an article

Critical appraisal is a systematic process used to identify the strengths and weaknesses of a research article in order to assess the usefulness and validity of research findings. The most important components of a critical appraisal are an evaluation of the appropriateness of the study design for the research question and a careful assessment of the key methodological features of this design. Other factors that also should be considered include the suitability of the statistical methods used and their subsequent interpretation, potential conflicts of interest and the relevance of the research to one's own practice. This Review presents a 10-step guide to critical appraisal that aims to assist clinicians to identify the most relevant high-quality studies available to guide their clinical practice.

Key Points

- Critical appraisal is a systematic process used to identify the strengths and weaknesses of a research article

- Critical appraisal provides a basis for decisions on whether to use the results of a study in clinical practice

- Different study designs are prone to various sources of systematic bias

- Design-specific, critical-appraisal checklists are useful tools to help assess study quality

- Assessments of other factors, including the importance of the research question, the appropriateness of statistical analysis, the legitimacy of conclusions and potential conflicts of interest are an important part of the critical appraisal process

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

206,07 € per year

only 17,17 € per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Making sense of the literature: an introduction to critical appraisal for the primary care practitioner

Article 23 October 2020

How to appraise the literature: basic principles for the busy clinician - part 2: systematic reviews and meta-analyses

Article 22 April 2022

How to appraise the literature: basic principles for the busy clinician - part 1: randomised controlled trials

Article 08 April 2022

References

- Druss BG and Marcus SC (2005) Growth and decentralisation of the medical literature: implications for evidence-based medicine. J Med Libr Assoc93: 499–501 PubMedPubMed CentralGoogle Scholar

- Glasziou PP (2008) Information overload: what's behind it, what's beyond it? Med J Aust189: 84–85 PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Last JE (Ed.; 2001) A Dictionary of Epidemiology (4th Edn). New York: Oxford University Press Google Scholar

- Sackett DL et al. (2000). Evidence-based Medicine. How to Practice and Teach EBM. London: Churchill Livingstone Google Scholar

- Guyatt G and Rennie D (Eds; 2002). Users' Guides to the Medical Literature: a Manual for Evidence-based Clinical Practice. Chicago: American Medical Association Google Scholar

- Greenhalgh T (2000) How to Read a Paper: the Basics of Evidence-based Medicine. London: Blackwell Medicine Books Google Scholar

- MacAuley D (1994) READER: an acronym to aid critical reading by general practitioners. Br J Gen Pract44: 83–85 CASPubMedPubMed CentralGoogle Scholar

- Hill A and Spittlehouse C (2001) What is critical appraisal. Evidence-based Medicine3: 1–8 [http://www.evidence-based-medicine.co.uk] (accessed 25 November 2008) Google Scholar

- Public Health Resource Unit (2008) Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP). [http://www.phru.nhs.uk/Pages/PHD/CASP.htm] (accessed 8 August 2008)

- National Health and Medical Research Council (2000) How to Review the Evidence: Systematic Identification and Review of the Scientific Literature. Canberra: NHMRC

- Elwood JM (1998) Critical Appraisal of Epidemiological Studies and Clinical Trials (2nd Edn). Oxford: Oxford University Press Google Scholar

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (2002) Systems to rate the strength of scientific evidence? Evidence Report/Technology Assessment No 47, Publication No 02-E019 Rockville: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality

- Crombie IK (1996) The Pocket Guide to Critical Appraisal: a Handbook for Health Care Professionals. London: Blackwell Medicine Publishing Group Google Scholar

- Heller RF et al. (2008) Critical appraisal for public health: a new checklist. Public Health122: 92–98 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- MacAuley D et al. (1998) Randomised controlled trial of the READER method of critical appraisal in general practice. BMJ316: 1134–37 ArticleCASGoogle Scholar

- Parkes J et al. Teaching critical appraisal skills in health care settings (Review). Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2005, Issue 3. Art. No.: cd001270. 10.1002/14651858.cd001270 Google Scholar

- Mays N and Pope C (2000) Assessing quality in qualitative research. BMJ320: 50–52 ArticleCASGoogle Scholar

- Hawking SW (2003) On the Shoulders of Giants: the Great Works of Physics and Astronomy. Philadelphia, PN: Penguin Google Scholar

- National Health and Medical Research Council (1999) A Guide to the Development, Implementation and Evaluation of Clinical Practice Guidelines. Canberra: National Health and Medical Research Council

- US Preventive Services Taskforce (1996) Guide to clinical preventive services (2nd Edn). Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins

- Solomon MJ and McLeod RS (1995) Should we be performing more randomized controlled trials evaluating surgical operations? Surgery118: 456–467 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Rothman KJ (2002) Epidemiology: an Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press Google Scholar

- Young JM and Solomon MJ (2003) Improving the evidence-base in surgery: sources of bias in surgical studies. ANZ J Surg73: 504–506 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Margitic SE et al. (1995) Lessons learned from a prospective meta-analysis. J Am Geriatr Soc43: 435–439 ArticleCASGoogle Scholar

- Shea B et al. (2001) Assessing the quality of reports of systematic reviews: the QUORUM statement compared to other tools. In Systematic Reviews in Health Care: Meta-analysis in Context 2nd Edition, 122–139 (Eds Egger M. et al.) London: BMJ Books ChapterGoogle Scholar

- Easterbrook PH et al. (1991) Publication bias in clinical research. Lancet337: 867–872 ArticleCASGoogle Scholar

- Begg CB and Berlin JA (1989) Publication bias and dissemination of clinical research. J Natl Cancer Inst81: 107–115 ArticleCASGoogle Scholar

- Moher D et al. (2000) Improving the quality of reports of meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials: the QUORUM statement. Br J Surg87: 1448–1454 ArticleCASGoogle Scholar

- Shea BJ et al. (2007) Development of AMSTAR: a measurement tool to assess the methodological quality of systematic reviews. BMC Medical Research Methodology7: 10 [10.1186/1471-2288-7-10] Google Scholar

- Stroup DF et al. (2000) Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA283: 2008–2012 ArticleCASGoogle Scholar

- Young JM and Solomon MJ (2003) Improving the evidence-base in surgery: evaluating surgical effectiveness. ANZ J Surg73: 507–510 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Schulz KF (1995) Subverting randomization in controlled trials. JAMA274: 1456–1458 ArticleCASGoogle Scholar

- Schulz KF et al. (1995) Empirical evidence of bias. Dimensions of methodological quality associated with estimates of treatment effects in controlled trials. JAMA273: 408–412 ArticleCASGoogle Scholar

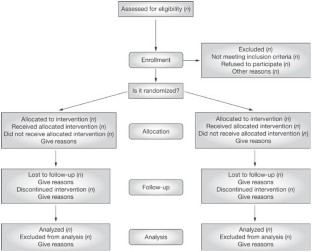

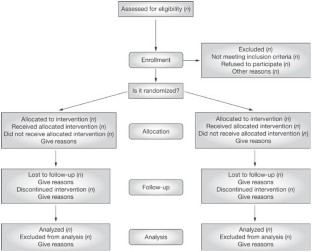

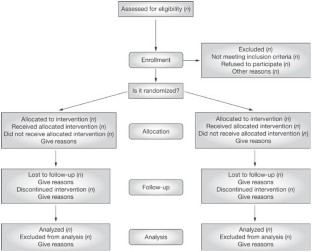

- Moher D et al. (2001) The CONSORT statement: revised recommendations for improving the quality of reports of parallel group randomized trials. BMC Medical Research Methodology1: 2 [http://www.biomedcentral.com/ 1471-2288/1/2] (accessed 25 November 2008) ArticleCASGoogle Scholar

- Rochon PA et al. (2005) Reader's guide to critical appraisal of cohort studies: 1. Role and design. BMJ330: 895–897 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Mamdani M et al. (2005) Reader's guide to critical appraisal of cohort studies: 2. Assessing potential for confounding. BMJ330: 960–962 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Normand S et al. (2005) Reader's guide to critical appraisal of cohort studies: 3. Analytical strategies to reduce confounding. BMJ330: 1021–1023 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- von Elm E et al. (2007) Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. BMJ335: 806–808 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Sutton-Tyrrell K (1991) Assessing bias in case-control studies: proper selection of cases and controls. Stroke22: 938–942 ArticleCASGoogle Scholar

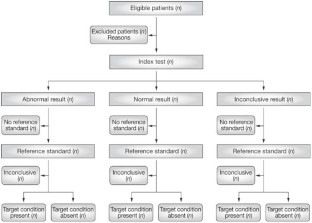

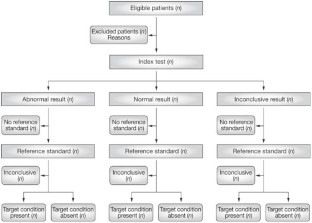

- Knottnerus J (2003) Assessment of the accuracy of diagnostic tests: the cross-sectional study. J Clin Epidemiol56: 1118–1128 ArticleCASGoogle Scholar

- Furukawa TA and Guyatt GH (2006) Sources of bias in diagnostic accuracy studies and the diagnostic process. CMAJ174: 481–482 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Bossyut PM et al. (2003)The STARD statement for reporting studies of diagnostic accuracy: explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med138: W1–W12 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- STARD statement (Standards for the Reporting of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies). [http://www.stard-statement.org/] (accessed 10 September 2008)

- Raftery J (1998) Economic evaluation: an introduction. BMJ316: 1013–1014 ArticleCASGoogle Scholar

- Palmer S et al. (1999) Economics notes: types of economic evaluation. BMJ318: 1349 ArticleCASGoogle Scholar

- Russ S et al. (1999) Barriers to participation in randomized controlled trials: a systematic review. J Clin Epidemiol52: 1143–1156 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Tinmouth JM et al. (2004) Are claims of equivalency in digestive diseases trials supported by the evidence? Gastroentrology126: 1700–1710 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Kaul S and Diamond GA (2006) Good enough: a primer on the analysis and interpretation of noninferiority trials. Ann Intern Med145: 62–69 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Piaggio G et al. (2006) Reporting of noninferiority and equivalence randomized trials: an extension of the CONSORT statement. JAMA295: 1152–1160 ArticleCASGoogle Scholar

- Heritier SR et al. (2007) Inclusion of patients in clinical trial analysis: the intention to treat principle. In Interpreting and Reporting Clinical Trials: a Guide to the CONSORT Statement and the Principles of Randomized Controlled Trials, 92–98 (Eds Keech A. et al.) Strawberry Hills, NSW: Australian Medical Publishing Company Google Scholar

- National Health and Medical Research Council (2007) National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research 89–90 Canberra: NHMRC

- Lo B et al. (2000) Conflict-of-interest policies for investigators in clinical trials. N Engl J Med343: 1616–1620 ArticleCASGoogle Scholar

- Kim SYH et al. (2004) Potential research participants' views regarding researcher and institutional financial conflicts of interests. J Med Ethics30: 73–79 ArticleCASGoogle Scholar

- Komesaroff PA and Kerridge IH (2002) Ethical issues concerning the relationships between medical practitioners and the pharmaceutical industry. Med J Aust176: 118–121 PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Little M (1999) Research, ethics and conflicts of interest. J Med Ethics25: 259–262 ArticleCASGoogle Scholar

- Lemmens T and Singer PA (1998) Bioethics for clinicians: 17. Conflict of interest in research, education and patient care. CMAJ159: 960–965 CASPubMedPubMed CentralGoogle Scholar

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

- JM Young is an Associate Professor of Public Health and the Executive Director of the Surgical Outcomes Research Centre at the University of Sydney and Sydney South-West Area Health Service, Sydney, Jane M Young

- MJ Solomon is Head of the Surgical Outcomes Research Centre and Director of Colorectal Research at the University of Sydney and Sydney South-West Area Health Service, Sydney, Australia., Michael J Solomon

- Jane M Young