Private health coverage is subject to significant requirements at the state and federal levels. While the Affordable Care Act (ACA) of 2010 ushered in many new requirements for the federal regulation of private health coverage, another federal law, the Employer Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA), has for over 50 years regulated the most predominant form of health coverage for people under age 65, employer-sponsored coverage.

States have traditionally been the primary regulators of health insurance and state health insurance protections continue to play a major role alongside a growing list of federal protections meant to address a variety of consumer concerns, from access to coverage to affordability and adequacy. This chapter describes the landscape of laws and regulations that address health care coverage and the complicated interactions between state and federal requirements that can make these protections challenging to navigate for consumers. In this chapter, it is not possible to cover every single state and federal requirement for private plans, so the focus is on the primary laws and regulations that apply to private insurance coverage.

Private health coverage is a mechanism for people to finance the health care services and medications they need, protecting them from the potentially extreme financial costs of this care.

At its core, health coverage is a financial contract between a private organization insuring the risk of loss and a policyholder. Where those insuring the risk or paying health claims are private entities such as insurance companies or private employers, this coverage is considered “private.” Coverage available in Health Insurance Marketplaces created by the ACA is considered private coverage, even though the Marketplaces are administered by state or federal government agencies. Public coverage, by contrast, involves financing arrangements for programs such as Medicare and Medicaid which are paid primarily from public sources. This includes private plans participating in Medicare Advantage and Medicaid managed care arrangements. (See the chapters on Medicare and Medicaid for more information.)

A fundamental concept for the private provision of health coverage is pooling the health care “risk” of a group of people to make the costs of coverage more predictable and manageable. The goal typically is to maintain a risk pool of people whose health, on average, is the same as that of the general population. Private health coverage regulation has historically included steps to prevent insurers and plan sponsors from avoiding people in poor health, while also ensuring that risk pools include people in good health to guard against “adverse selection.”

A risk pool with adverse selection that attracts a disproportionate share of people in poor health, who are more likely to seek health coverage than people who are healthy, will result in increased costs to cover those in the pool, leaving those in better health to seek out a pool with lower costs.

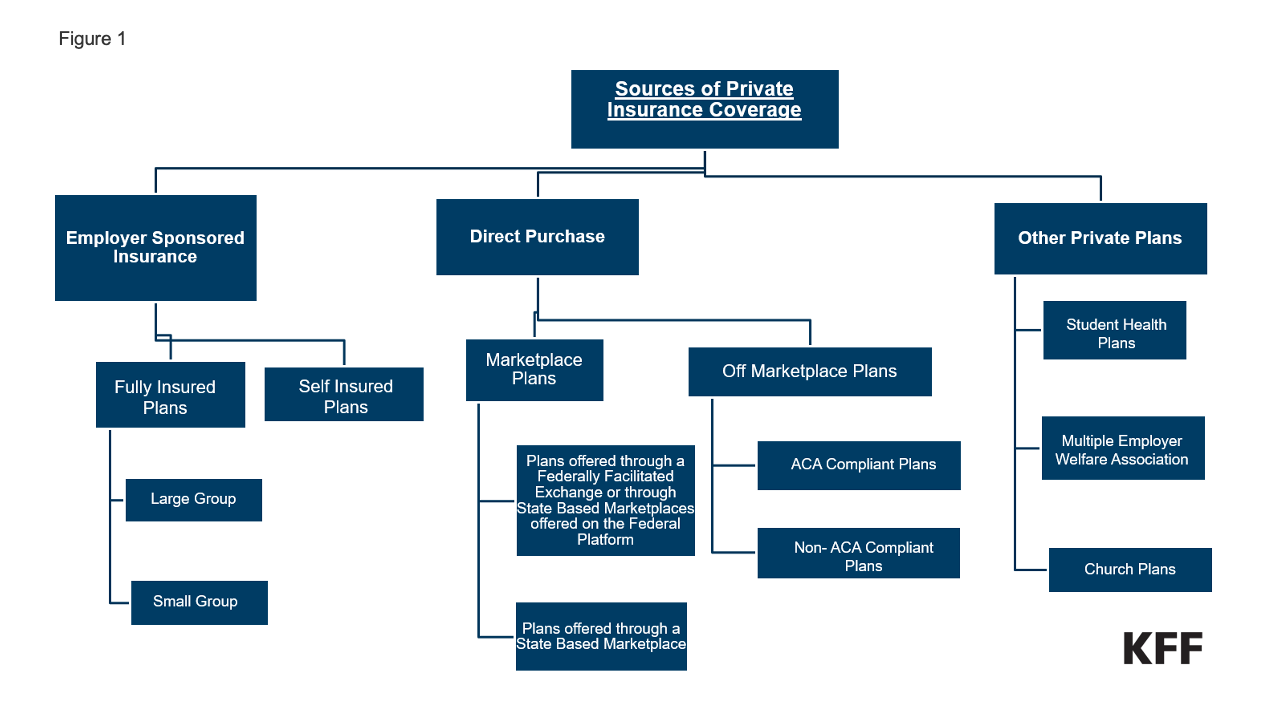

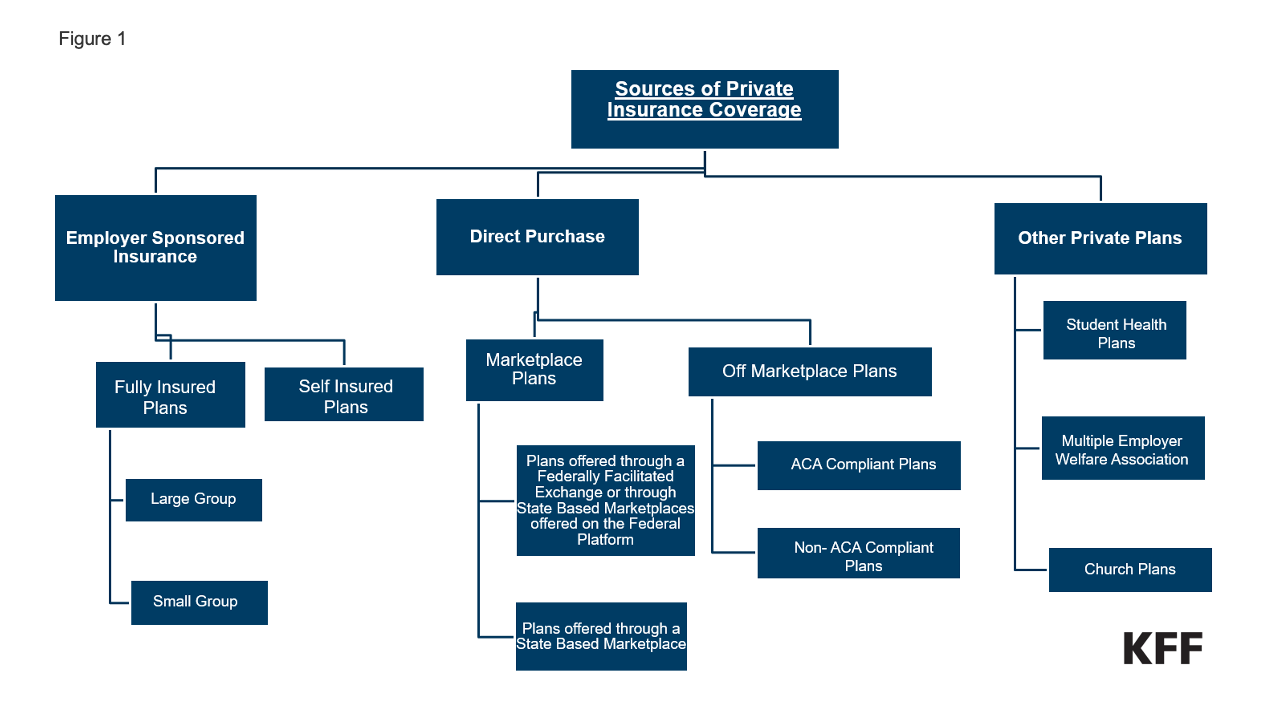

Sources of private coverage. An individual with private coverage generally obtains it through one of two sources, either through their employer (“group” coverage) or by directly purchasing it from an insurer (“nongroup” coverage). There are other related sources of coverage that don’t exactly fit into one of these two categories, such as coverage provided by professional associations.

1. Employer coverage: In 2023, about 165 million people under age 65 had coverage through an employer. Employer-sponsored coverage is offered to eligible employees and usually also to employees’ dependents, such as spouses and children. This coverage is referred to as “group” coverage, which is further broken down into small-group or large-group depending on the number of employees. (See diagram above.)

Private employers who “sponsor” group health plan coverage could include a range of entities, from a single nationwide retail employer with thousands of employees in many states to a small “mom and pop” operation with a handful of employees in one location. A single union can also be a group health plan sponsor of private coverage as an “employee organization,” as well as entities called “multiemployer” plans that are collectively bargained entities run by a joint board of trustees from labor and management that oversee collectively bargained benefits provided to employees of more than one employer, often in the same industry (for example, hotel workers or skilled workers in the building trades).

Public employers—federal, state or local government—also sponsor group health coverage.

Employers, private and public, have at least two approaches to make coverage available to employees:

2. Individually-purchased insurance coverage: An individual can purchase private health coverage for themselves and their family without the involvement of their employer, referred to as “nongroup” coverage. Every state has an “individual insurance market” that consists of the following:

3. Other Sources of Private Health Coverage: Other sources of health coverage subject to unique regulatory standards include health coverage provided through entities called “multiple employer welfare arrangements” (MEWAs), “church plans,” and coverage provided by colleges and universities for their students.

Most private plans utilize a “network” of health care providers and hospitals, with some plans requiring a referral from a primary care provider (PCP) for enrollees to see a specialist. These types of arrangements, referred to as “managed care plans,” attempt to control costs and utilization through financial incentives, development of treatment protocols, prior authorization rules, and dissemination of information on the quality of provider practices.

Most private health coverage, whether employer-sponsored or individually purchased, falls into one of the following types:

All of these plan types are available in the individual market, both on and off the Marketplace. Most employers that offer health benefits offer just one type of health plan, though larger firms may offer more. PPOs are the most common type of health plan offered by employers.

Other employer-sponsored health coverage arrangements: Employers also often offer a Health Reimbursement Arrangement (HRA), which is an employer-funded group health plan, sometimes paired with an HDHP, that reimburses an employee up to a certain amount for qualified medical expenses and, in some instances, health insurance premiums. Reimbursements are tax-free to the employee and amounts in the account can carry over to the following year, but employees lose any amounts when they leave the employer. Other variations of HRAs include an Individual Coverage HRA (ICHRA) where an employee can use funds in the HRA to purchase individual insurance either on or off the Marketplace. Qualified Small Employer Health Reimbursement Arrangements (QSHRAs) are HRAs that certain small employers can make available for tax-free reimbursement of certain expenses.

Some private health plans utilize “value-based” coverage and alternative payment models. These designs, primarily used in federal Medicare and Medicaid demonstration projects, aim to make providers more accountable for patient outcomes through various financial and other incentives. The objective of value-based care design is to shift the fee-for-service reimbursement model of paying for care based on “volume” to a system that pays based on the “value” of a service. Demonstration results to date have not shown major savings, but these designs are still discussed as a potential cost-containment tool for private health coverage. Payers and providers have also looked to value-based payment models to improve health disparities and to provide more patient-centered care.

The regulatory framework for private health coverage has evolved into a complicated system of overlapping state and federal standards. This federalism framework creates a sometimes precarious “marriage” between state and federal authority in order to implement health policy goals.

The regulation of insurance has traditionally been a state responsibility. States license entities that offer private health insurance and have a range of insurance standards, including financial requirements unique to state law. However, the federal government has played an increasingly significant regulatory role over the past 50 years.

The federal pension law, ERISA, passed in 1974, applies to insured and self-insured private employer-sponsored health coverage with similar legal and enforcement mechanisms to protect individuals covered by private group health plans as those created for pension plans.

Separately, the federal Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA) created new federal requirements and the basic framework for how state and federal law now interact. Under this “federal fallback” structure, states may require that insurers in the group and individual market (as well as state and local government self-insured plans) implement federal requirements on health coverage. If a state fails to “substantially enforce” the federal requirements, the federal government will enforce those protections. The federal fallback framework was intended to allow states to continue to regulate private coverage while ensuring that all consumers nationwide have a floor of federal protections when a state fails to implement them.

The federal fallback framework does not apply to self-insured employer-sponsored coverage. The U.S. Department of Labor (DOL) almost exclusively regulates private self-insured employer-sponsored plans. The Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) directly enforces federal protections against state and local government self-insured employer plans (although states can do so too).

ERISA specifically “preempts” or prevents state law from applying to most self-insured group health plans, limiting the scope and application of state protections for many Americans covered by employer-sponsored plans.

Aspects of this preemption have been the topic of almost 50 years of litigation, resulting in three overall conclusions:

Today, some argue that ERISA preemption sustains the employer-based health coverage system because meeting an ever-growing list of state laws would be costly for employers, particularly those with employees in multiple states. Having national uniform standards, they argue, provides employers with an incentive to offer coverage. Others argue that preemption handcuffs states’ ability to protect consumers and control health care costs and is no longer needed given the ACA’s employer coverage mandate for larger employers and the increased regulation that applies a variety of rules to both fully-insured and self-insured plans. Prospects for change are limited, but some have explored the possibility of alternative approaches.

Private health insurance regulations vary based on the insurance market and the source of coverage. This is in part due to ERISA preemption and the ACA, which applies many reforms only to the individual and small-group markets.

Further complicating this are plans that existed before the ACA was passed, called “grandfathered” plans, that do not have to meet many of the ACA standards so long as no significant changes in cost sharing and benefits are made to the plan.

The ACA did, however, alter federal law to create a large number of consumer protections that apply many of the same regulatory requirements across almost all sources of private health coverage.

Finally, some federal standards only apply to employer-sponsored plans (insured and self-insured) that are governed by ERISA, such as the requirement on employers with 20 or more employees to provide temporary continuation of coverage in certain situations, known as COBRA, which also applies to certain state and local government employers. There are also obligations on plan "fiduciaries" that are unique to ERISA plans.

This all means consumers can have different legal protections with their private coverage based on their coverage type and the state where they live.

Some private plans are specifically exempt from most federal private health coverage protections, including the ACA. These forms of coverage are often called “non-ACA compliant” coverage. While “non-ACA compliant” does not automatically mean it is illegal or inappropriate, some forms of this coverage have come under increasing scrutiny by federal and state authorities due to their gaps in consumer protections.

These types of coverage fall into these general categories:

Some of these forms of coverage are the focus of business promoters looking to market cheaper, largely unregulated forms of coverage. In some instances, this coverage might be promoted by unscrupulous actors who falsely market the coverage as meeting ACA requirements or as providing comprehensive coverage. In other cases, coverage is sold as supplemental “health” coverage along with ACA-compliant health insurance sometimes with very high deductibles. These exceptions to the ACA’s broad coverage requirements can operate as loopholes in the implementation of consumer health coverage protections and may create ambiguities for consumers as well as employers.

Central to evaluating how private coverage works are the tax subsidies that reduce the cost of coverage and benefits, which can incentivize employers to sponsor and individuals to purchase private health coverage. Tax regulations also define what is a health expense that gets a tax preference.

The largest health care tax subsidy is applied to employer-sponsored coverage. Tax-exempt employer contributions for medical insurance premiums and medical care resulted in more than $224 billion in lost revenue for the federal government in 2022. Employer-sponsored health coverage is excluded from federal income tax, as well as federal employment taxes (and equivalent state taxes). The exclusion also applies to amounts reimbursed to employees by an employer under arrangements called “health flexible spending arrangements” (health FSAs), where an employee elects to have amounts withheld from their wages to pay for medical expenses. The exclusion provides considerable tax savings for employers and employees making contributions toward health coverage. The value of this exclusion increases as income increases, making income tax savings greater for higher-income individuals than for lower-income individuals. For various policy reasons, including to rein in health care costs, there have been efforts to change or cap this exclusion over the years, but to date, none have been successful. The most recent, the “Cadillac tax” provision of the ACA, was removed from the law before it was implemented (see employer chapter).

Additionally, the ACA created refundable tax credits based on household income to help individuals purchase coverage on a health insurance Marketplace (see ACA chapter). In contrast to the employer exclusion, tax subsidies for Marketplace participants are higher for those with lower incomes. Temporary increases in these credit amounts, passed as part of the American Rescue Plan and the Inflation Reduction Act, have led to record Marketplace enrollment. The temporary increases expire at the end of 2025 and will end unless extended. Unlike employer-sponsored insurance, Marketplace enrollees who pay a premium for their coverage do so with after-tax dollars.

The scope and extent of federal regulation that affects private health coverage has vastly increased, especially with the passage of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) in 2010. As stated earlier, the ACA largely retained the framework for the regulation of private coverage, adding a long list of new provisions to different regulated pieces of our fragmented health care system. This means specific and overlapping requirements on insurers, employer-sponsored plans, and, more recently, in the No Surprises Act, also on providers.

The ACA also unleashed a firestorm of activity resulting from longstanding political and philosophical differences on the role of federal government regulation of health care. Efforts to repeal and replace the ACA, several U.S. Supreme Court cases challenging ACA provisions, and hundreds of other cases in the lower courts on the ACA and other federal requirements mean the law in this area has and will continue to be in flux.

Regulatory priorities can and have shifted depending on what party controls the White House and Congress, resulting in ever-changing federal standards. This section reviews the current landscape of federal requirements. A discussion of every single relevant federal regulation is beyond the scope of this chapter, but the major requirements have been divided into six categories:

Federal health care reform has prioritized expanding health coverage to those without it for quite some time, especially for those not eligible for a public program such as Medicaid or Medicare, or who do not have coverage through their current employer. Prior to the passage of the Affordable Care Act in 2010, state laws and regulations were designed to address the potential for adverse selection in health insurance by allowing insurers to engage in certain practices such as “underwriting,” which allowed insurers in the individual and group markets to decline to cover or renew coverage due to a person’s health status or a group’s claims history, and helped plans maintain predictable and stable risk pools. Further, an insurer could cover the applicant, but charge a higher premium based on age, health status, gender, occupation, or geographic location. In addition, insurers could exclude benefits for certain health conditions if the person was diagnosed or treated for that condition prior to becoming insured (a “preexisting condition exclusion”).

States made some reforms, particularly in the small group market, to address these barriers to coverage. Some of these changes became part of the federal Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) of 1996. However, it was not until the ACA that the regulation of private insurance, at least the individual and small group markets, was fundamentally changed.

Core Private Insurance Coverage Protections. The ACA established core market rules designed to expand coverage to most people in the U.S. New ACA legal requirements include:

Requirements for premium stabilization & other efforts to protect the risk pool. The ACA’s private insurance market regulations also ushered in concerns that its protections, including guaranteed issue and the elimination of health underwriting for some coverage, would result in adverse selection (discussed in the first section). Regulatory efforts to prevent adverse selection have also focused on certain plans and products that do not have to meet most of the ACA rules, such as short-term limited-duration plans. Non-ACA-compliant coverage may be attractive to consumers looking for lower monthly costs, but these plans can leave consumers underinsured and may compromise the risk pool by drawing out healthier individuals.

Federal guidance and regulation aimed at protecting the risk pool as part of the ACA include:

Standards to prevent coverage gaps. Access to coverage is also enhanced by federal requirements to provide for the continuity of coverage or care to prevent gaps for those who do or could lose coverage, including:

High costs, in the form of both premiums and cost sharing, have been a defining feature of employer-sponsored and individually-purchased (for unsubsidized enrollees) health coverage. Federal reforms have sought to address the stability and affordability of health insurance. Key provisions include:

Federal requirements also include a growing list of minimum standards for how a plan is designed or operated in an effort to ensure that enrollees have coverage that is comprehensive enough to cover medically necessary care, with processes that do not unnecessarily limit access to covered benefits. Such requirements include laws that prohibit plans from imposing annual dollar limits on coverage, requiring waiting periods longer than 90 days before employer-sponsored coverage kicks in. States may have additional benefit mandates for state-regulated plans, such as comprehensive coverage requirements for state-regulated plans, such as comprehensive coverage requirements for mental health or substance use disorders or fertility services.

Required coverage

The ACA requires all private, non-grandfathered health plans to cover preventive services with no cost sharing for enrollees. These requirements change over time as preventive service recommendations are updated and new services are added. In general, these include:

The preventive care coverage requirement has been the subject of extensive litigation since the ACA was passed. A KFF brief provides more detail on this litigation. The contraceptive coverage requirement has been the topic of two U.S. Supreme Court cases and several regulations, now allowing employers to not cover contraception if they have a religious objection.

Other required design standards across most health plans

Large group, small group, individual, and self-insured health plans are required to abide by other benefit design standards that aim to contain out-of-pocket costs and improve access to and quality of care. These design standards include:

Design standards limited to individual and small group plans. Federal requirements on health plan design standards for certain segments of the individual and small-group markets have evolved since the ACA was passed. Plans must meet these rules as part of annual certification requirements for qualified health plans. Examples of these standards include:

In the 2023 KFF Consumer Survey of insured adults, most Marketplace and employer-sponsored insurance (ESI) enrollees reported difficulty understanding some aspect of their health insurance compared to consumers enrolled in Medicaid and Medicare:

Lack of information or understanding about key features of an individual’s health coverage can put patients at financial risk and result in negative health outcomes. Employers and other health purchasers have also struggled to get the information they need to make prudent decisions about cost-effective coverage options and hold their service providers accountable for their plan designs, contracting, and administration activities. Regulations have increased over time to make more information available to enrollees or prospective enrollees, as well as to federal agencies to conduct their oversight responsibilities. What to disclose and how much information is useful is a continuing policy challenge.

Most federal disclosure, reporting, and transparency requirements fall into two categories: Disclosure of information to enrollees and/or the public (Table 9) and reporting to the federal government (Table 10). Note that the requirements provided in these tables are not exhaustive, but include examples of some of the main reporting, disclosure, and transparency requirements that plans, providers, and facilities are subject to.

Ongoing reporting by private plans to federal agencies is a tool for agency oversight to assess compliance with regulations and evaluate trends. In some instances, agencies are required to use this information to report aggregate information to the public and Congress.

Access to a fair system of review for consumer grievances about plan actions and claims denials has been a key element of federal consumer protection.

A 1997 Clinton Administration initiative, the Patient Bill of Rights, resulted in several federal agencies taking regulatory actions to enhance consumer protections for patients and workers. As part of this initiative, the DOL updated claims and appeals rules that applied to private-sector employer plans regulated by ERISA to make the claims review process:

The DOL issued regulations in 2000 governing the “internal” claims review process, conducted internally by a plan or plan-sponsor employer. For the first time, these updated rules accounted for managed care features such as prior authorization, whereby health plans determine medical necessity before the plan covers an item or service, requiring, for example, shorter time frames for claim decisions and appeals for these “pre-service” claims.

These rules were the basis for reforms applied across all private health coverage in the ACA. These reforms provided a federal floor of protections for the internal claims and appeal process and added an option for consumers to appeal a denied claim and an appeal process for review by an entity independent of the plan in a process called “external review.” Only certain types of claims, such as those that involve clinical judgment, are eligible for external review.

Policymakers have renewed scrutiny of the prior authorization process as well as claims review and appeals generally. Claims and appeals standards that apply to Medicare Advantage plans, Medicaid, and some Marketplace plans have recently been updated to reduce delays in decision making and to provide more transparency about the outcomes of claims and appeals decisions.

Several other federal laws and regulations provide consumer protections in private health insurance, often indirectly, that sometimes have stronger enforcement mechanisms and penalties than federal insurance laws. These include:

Civil Rights Law. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 (and later amendments to it, including the Pregnancy Nondiscrimination Act) and the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 created protections against discrimination based on race, color, national origin, sex, age, and disability. At a minimum, these standards apply to employers with 15 or more employees, and, in effect, regulate those employers’ group health plan coverage.

Section 1557 of the ACA included a nondiscrimination provision that potentially applies many existing civil rights laws directly to health care entities, including insurers that receive federal funds. The extent of its reach has been the subject of several sets of regulations, with the latest under the Biden Administration finalized in 2024. The rule reinstates protections against discrimination for LGBTQ+ people seeking health care and coverage, including for gender-affirming care.

Antitrust Laws. Antitrust laws in health care prohibit anticompetitive practices and mergers by health care providers, hospitals, and insurers, which can reduce competition and increase prices. As provider consolidation increases, federal agencies such as the DOJ and the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) have ramped up enforcement initiatives in recent years, as outlined in a KFF brief. Health insurers have also faced antitrust scrutiny as the market shares of the largest health insurers continue to dominate in most locations. Oversight of pharmacy benefit managers, now mostly owned or affiliated with the leading health insurers, is one area of focus.

Privacy Laws. As digital technology has advanced, so have policy concerns about protecting consumer health information, as the fast development of new technology (e.g. health-related apps) has made it difficult for regulation to keep up. The leading federal privacy requirements for health plans’ use of certain patient information, set out in HIPAA regulations, are now almost 25 years old. Efforts to update this regulation are underway, including specific standards for information regarding abortion after the Supreme Court invalided the constitutional right to abortion in 2022. In addition, the Federal Trade Commission has sought to regulate areas not covered directly by HIPAA, such as software applications increasingly marketed as part of health coverage.

Special privacy protections for substance use disorder information are regulated under a law known as “Part 2.” This law aims to protect the confidentiality of this information while still allowing providers to share patients’ mental health and substance use disorder information with plans and others to coordinate care and administer benefits.

Gag Clauses. Plans and issuers are prohibited from entering into an agreement with a provider, third-party administrator, or other service provider (including pharmacy benefit managers) that restricts the plan and issuer from accessing claim, cost, or quality information on providers, enrollees, plan sponsors, and other entities, known as a “gag clause.” Plans and issuers must annually submit an attestation of compliance with these requirements to the federal government.

Three federal agencies have overlapping jurisdiction for most federal regulation of private health plans: the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), the U.S. Department of Labor (DOL), and the U.S. Treasury Department. Through a structure created by HIPAA in 1996, these three agencies jointly issue regulations and other guidance on laws passed by Congress that place the same or similar standards across all private plans.

The same or similar federal requirements for private health plans are typically contained in three separate statutes that each agency oversees:

As an example, if Congress passes a federal law that requires all insurers of individual and group coverage and all employer-sponsored plans to meet a certain standard, any regulations issued to implement that standard are usually issued jointly by HHS, DOL, and Treasury with separate but identical language added to the Public Health Service Act (PHSA), ERISA, and the Internal Revenue Code (IRC). However, each agency has its own requirements for how these laws are enforced. In addition to these overlapping authorities, each of these three agencies has exclusive federal authority over certain aspects of private health insurance regulation (though the federal authority might be shared with states in some instances):

Other agencies with important oversight roles of private health coverage include:

As the executive branch of the U.S. government, the federal government has the authority to execute laws passed by Congress and signed by the President, including by issuing regulations to operationalize and implement a statute. In addition, specific agencies have authority to investigate violations of the law and enforce the law through policy form review, market conduct exams, and by the assessment of penalties and/or bringing a court action to stop an insurer from violating the law (injunction).

Regulations and Other Guidance

Process: The federal regulatory process is governed primarily by the Administrative Procedure Act (APA). This law, along with specific executive orders, governs the process known as “notice and comment rulemaking,” where regulations are proposed (through a notice of proposed rulemaking or “NPRM”) and are subject to public comment for a certain period of time and then finalized. The process is administered by the Office of Management and Budget (OMB), an agency within the Executive Office of the President. The OMB’s Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs (OIRA) coordinates the review and release of regulations from the agencies. Regulations are published in the Federal Register, a daily publication of regulations and notices. Information about regulations under OIRA review are available by agency at Reginfo.gov, and the public can view all regulations and comment letters at Regulations.gov. Twice a year, OMB issues a regulatory agenda of regulations agencies expect to publish in the coming months.

Authority: Once a regulation has gone through the notice and comment process and a final rule issued, it is generally considered to have the force of law, meaning private actors must comply with it, and individuals can rely on having the protections set out in the law and the regulation. However, regulations are subject to legal challenge under the APA if they are inconsistent with the statute.

Review of regulations by courts: Traditionally, if a regulation interprets a part of the statute that was not clear as drafted by Congress, when a federal court reviews a challenge to the regulation, the court will uphold the interpretation in a regulation unless it is unreasonable or arbitrary. Essentially, courts have deferred to the expertise of government regulators and the regulatory review process to uphold a regulatory requirement if they deem the interpretation reasonable. This is called “Chevron deference,” named after a Supreme Court case from 1984, Chevron v. Natural Resources Defense Council, that set out the framework for court review of ambiguous language in a statute. This standard of review can result in agencies having discretion to implement policy changes through interpretation in regulation. That discretion has been challenged in recent years as too broad, giving regulators too much authority, and in June 2024, the U.S. Supreme Court overruled its previous decision, meaning federal courts will no longer be required to defer to regulations of administrative agencies in circumstances where they traditionally would have. Eliminating Chevron deference could weaken the impact of regulation on public policy and shift more policy decisions to courts.

Sub-regulatory guidance: Other types of information and guidance commonly issued by a federal agency that do not go through the formal regulatory notice and comment process are referred to as “sub-regulatory.” Information and interpretation in sub-regulatory guidance usually do not have the force of law as regulations do, and typically do not create legally binding obligations on private parties. They are, however, useful in quickly communicating information to regulated entities and the public to signal how and when the agency plans to implement a new law, and the timing of that implementation. However, reliance on these types of guidance by consumers has its limits since regulated entities might still assert that this type of guidance is not binding on them. Examples of sub-regulatory guidance include:

Enforcement

Given the federal fallback framework described in previous sections, the enforcement mechanism for most federal requirements on private coverage depends on the type of health plan and the federal agency enforcing the requirement, as summarized in Table 13 below.

Government enforcement. Under the existing federal fallback framework, CMS has developed a process for making a determination about whether a state is substantially enforcing each specific federal insurance protection. This means that whether a state or CMS is responsible for enforcement can differ for each health coverage standard, resulting in a patchwork of federal and state enforcement responsibilities.

Private Right of Action and Remedies. Some laws also allow individual consumers or their representatives to bring a lawsuit independent of the government to address a violation. These laws may detail what types of “remedies” are available if the challenge is successful---for example, an injunction to stop a violation, a civil penalty, compensatory or punitive damages. Without this “private right of action,” aggrieved consumers must rely solely on the government to act to address a problem.

The federal fallback framework also applies to most of the requirements on health care providers and facilities that are now part of federal law. In 2020, Congress passed the Consolidated Appropriations Act (CAA) which includes new protections on balanced billing (the No Surprises Act) and various provider rules regarding disclosure and transparency. States are expected to enforce these standards against providers, with CMS as the federal fallback. State health departments or state agencies that oversee provider and facility licensing and practice standards oversee these rules. CMS has surveyed states and entered into collaborative enforcement agreements with each state, including which CAA rules the state is prepared to enforce and which ones CMS will need to implement. CMS can assess a penalty of up to $10,000 per violation against a provider or facility for non-compliance.

Enforcement of other standards. Outside of the above federal fallback framework, each agency has its own separate enforcement mechanisms for the laws they implement alone. For instance, HHS has authority to assess fines under HIPAA privacy rules for violations, but individuals harmed by a HIPAA violation do not have a private right of action under that law. Enforcement processes and remedies available under federal nondiscrimination requirements under the Civil Rights Act or the Americans with Disabilities Act vary, but some include monetary damages in the form of compensatory damages.

The McCarran-Ferguson Act, enacted in 1945, clarified federal intent that states have the primary role in regulating the business of insurance. Although changes have since been made to that law, states have several mechanisms in place to regulate insurance. States license entities that offer private health coverage in a process that reviews the insurer’s finances, management, and business practices to ensure it can provide the coverage promised to enrollees. States also license the insurance agents and brokers in the state (more details in a later section).

State insurance laws and regulations vary by state though commonly include:

Most states require health plans to provide specific data that is included in the state’s all-payer claims databases (APCDs), which are state databases that include medical, pharmacy, and often dental claims, and eligibility and provider files collected from and aggregated across all private and public payers in a state. APCDs can provide states with a perspective on cost, service utilization, and quality of health care services across the full spectrum of payers in a state, which can be a tool in state efforts to control health care costs and promote value-based care.

Some states are also developing additional state-level regulations related to health plan network adequacy, health plan price transparency, public option plans, reinsurance programs, and more. These state-level regulations and protections do not apply to enrollees in self-insured plans (see earlier section for more information) offered by private employers. However, these enrollees may have some of these protections through similar federal laws and regulations.

State legislatures enact state insurance laws and typically grant regulatory authority to the state’s insurance regulator/commissioner. State enforcement mechanisms vary widely by state, regulation, state resources, and staffing capacity; shifting political priorities at the state level can also influence enforcement priorities and actions. For example, state insurance agencies may ensure compliance with certain benefit mandates by primarily relying on complaints from consumers, consumer advocates, or health care providers to trigger a compliance review of the plan in question, while other state insurance agencies conduct periodic systematic reviews of all plans subject to the law or regulation.

Navigating an increasingly complicated health coverage landscape has increased the focus on the availability and expertise of entities that assist purchasers of health coverage (consumers and employers). Assisters can include agents and brokers who are paid commissions from insurers, as well as consumer assistance entities, often publicly funded and nonprofit, who may provide similar assistance as agents and brokers, but also specialize in individuals transitioning in and out of public programs such as Medicaid or assisting those without insurance to find coverage.

Agents and brokers have long played an important role in connecting people and employers to private health coverage by helping them understand health insurance options and costs. An “agent” typically represents a single insurer and provides information about that insurer’s coverage options. A “broker” is not aligned with any one insurer but could, in theory, place coverage from any insurer selling products in a state.

Agents and brokers assist individuals in choosing a qualified health plan on a health insurance Marketplace. In the 2020 plan year, almost half (48%) of ACA coverage was sold through health insurance agents or brokers, up from 40% in plan year 2017. Web brokers, those who facilitate plan selection online through Marketplace capabilities, have also played a large role in Marketplace enrollment.

Even prior to the creation of the Marketplaces, agents and brokers have played a large role in selling coverage in the individual and group insurance market, especially to small employers needing expertise in finding health insurance for their employees. Large employers also use agents and brokers, who often work for employee benefit consultants or brokerage firms and receive commissions for finding vendors to support their self-insured group health plan or placing other forms of insurance that they provide or make available to employees as “voluntary” benefits.

Broker Compensation Reporting. Employer plans governed by ERISA must meet ERISA fiduciary standards. These standards prohibit plans from contracting with a “party-in-interest,” essentially an entity that may have a conflict of interest because they are receiving compensation from a third party for activity they are doing for the employer plan. For instance, a benefits consultant may be helping an employer find a third-party administrator (TPA) for its group health plan. Consider a situation in which the consultant is paid by the employer for their work, but the consultant also gets a commission from the TPA if the employer decides to use them. Employers are prohibited from entering into this type of transaction with the consultant unless they can show it was done in a reasonable manner.

Under rules added to ERISA by the Consolidated Appropriations Act (CAA), one way an employer plan can show their contract with a broker/consultant is reasonable is to show that they received information from the broker/consultant about the compensation the broker/consultant received from the TPA. Under these rules, an employer plan fiduciary violates ERISA if it does not receive from a broker or consultant information about the direct and indirect compensation the broker receives. Insurers offering individual insurance (on and off Marketplace), as well as those offering short-term limited duration coverage must disclose to enrollees and report to CMS any direct or indirect compensation they pay to agents and brokers for enrolling individuals in this coverage.

Other Types of Assisters. Other types of assisters for private health coverage were created by the ACA requirements for Marketplaces to establish Navigator programs to raise public awareness and to assist individuals to enroll in qualified health plans. Related assisters include “certified application counselors.” Most of these entities rely on federal or state funding to operate. The ACA also created separate Consumer Assistance Programs (CAP), which offered federal funding for states to create programs to assist consumers with insurance problems and identify their best options for health coverage. Unlike the Navigator program that was specifically created to assist Marketplace, Medicaid, and CHIP consumers, the CAP program was also created for those states that chose to apply to assist consumers with employer coverage as well as those with other types of coverage. Federal grant funding in 2010 allowed 35 states and Washington, D.C. to create CAPs. No grant funding has been made since then, eliminating the only federally funded program that could assist those with employer coverage. Many states have continued their CAP programs through their own funding but others have discontinued their operations.

The ACA and related reforms have significantly reduced the number of people in the U.S. without any health coverage, but the growing cost of care and the resulting increase in out-of-pocket consumer costs for those with coverage—a problem that existed before the ACA—will continue. Amidst increasing patient and consumer protections at the federal level, states still play a significant role in regulating private health insurance, creating a complex relationship between federal and state regulations that can result in a patchwork of different standards by market segment and state. The future regulatory outlook for health coverage hinges on key areas:

The limits of regulation. Challenges to federal agency power, and other long-standing approaches to how courts review agency regulation, have added legal hurdles to the implementation of existing law through regulation. The U.S. Supreme Court issued major decisions in 2024 to further limit agency discretion, handing more power to federal courts in the policymaking process. The implications of these decisions are far-reaching and will have profound effects on health policy for years to come.

State regulation of insurance. States will continue to play a significant role in shaping coverage and consumer protections in private insurance. Some recent examples of state activity include requiring state-regulated plans to cover certain reproductive health services such as coverage of fertility benefits and abortion services, and regulations related to prior authorization, transparency, and prescription drug coverage and costs that go beyond what federal law requires. The scope of some of these efforts will be limited due to ERISA preemption for most self-funded employer plans.

A focus on oversight. As public insurance programs have increased the coverage provided through private health plans (Medicare Advantage and Medicaid managed care plans), new inquiries from the federal government and state governments on their managed care practices, such as prior authorization and provider network design, have resulted in renewed focus on how these practices have been working in private health insurance as well. Expect more questions about how internal insurance processes such as claims review are working and enforced, and whether the tradeoffs between cost and coverage inherent in these processes are leaving patients without coverage for medically necessary care.

Getting ahead of technology changes. Expect wide ranging recommendations from major stakeholders on what aspects of AI and telehealth should be nurtured, and which ones should be regulated. Since the regulatory process is slow, much of the future outlook will ride on the voluntary actions of industry and how transparent those activities are. Updates to longstanding privacy rules will also try to catch up to improved technology capabilities. Additionally, new, expensive gene therapies and blockbuster medications will also challenge policy makers to rethink existing structures of reimbursement and government intervention in pricing.

Assessing whether consumers are getting what they pay for with their health coverage. In the coming years, there will be a better ability to assess whether regulatory initiatives that focus on transparency made any difference for the patient in their day-to-day decision making and access to information about their coverage. Medical debt and ways to prevent it are also growing concerns, especially for those with health coverage and chronic illnesses. Additionally, data that measure consumer outcomes in understanding and usability of coverage, and health equity in coverage and care will be important going forward.